Brains Under Construction: Why Teens Take Risks

Understanding the brain science and behavior patterns behind teens' risky decisions.

Adult": “Why did you do that?”

Teen: “Because it seemed fun.”

Adult: “Did you know it was dangerous?”

Teen: “Yeah… but I still wanted to try.”

Sound familiar?

If you’ve ever parented, taught, or mentored a teenager, you’ve likely witnessed some head-scratching choices. But here’s the truth: risk-taking in adolescence isn’t just common - it’s developmentally expected.

Today, let’s unpack what drives teens to take risks, what kinds of risk-taking we should (and shouldn’t) worry about, and how you can support safe independence without squashing curiosity.

Key Concepts

The Adolescent Brain is a Work in Progress

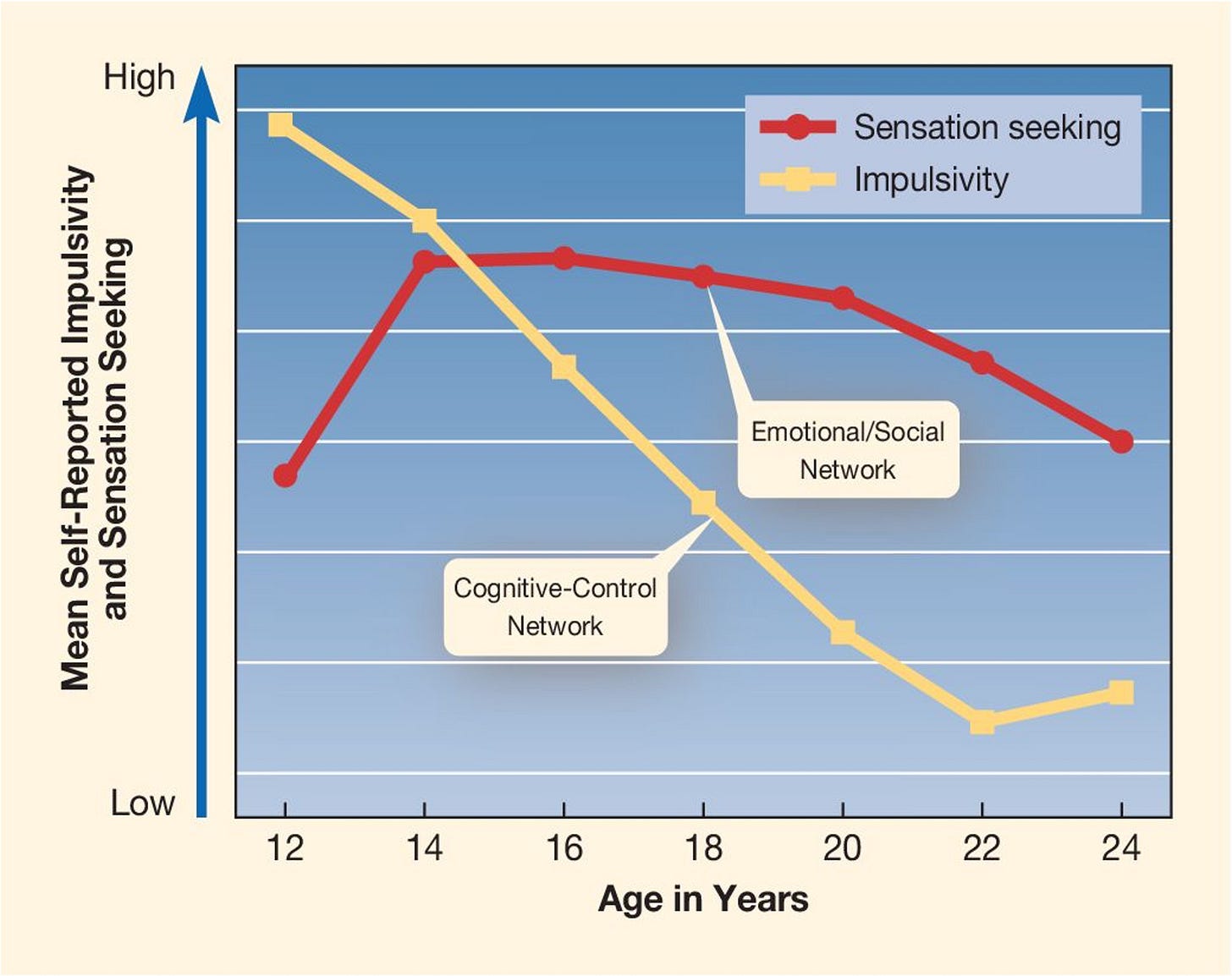

The limbic system (which processes emotion and reward) becomes highly active in early adolescence.

The prefrontal cortex (responsible for judgment, impulse control, and long-term planning) doesn’t fully mature until the mid-20s.

This mismatch explains why teens are more likely to feel intensely and act impulsively, even when they understand the consequences.

It’s like driving a car with a powerful engine (reward system) and half-built brakes (prefrontal cortex).

Two Types of Risk-Taking (Moffitt, 1993)

Developmental psychologist Terrie Moffitt identified two broad groups of teen risk-takers:

Adolescence-Limited (what we are focused on today):

Risky behavior starts in the teen years and tapers off in adulthood

Usually peer-driven and temporary

Part of a healthy desire for autonomy

Life-Course-Persistent:

Problem behaviors begin in early childhood and persist over time

Often linked to neurodevelopmental difficulties or chronic stress

May require early intervention and sustained support

This framework helps us avoid overreacting to normal adolescent behavior - and recognize when something more serious may be developing.

Research Spotlight

Albert et al. (2013) found that teens are more likely to take risks in peer settings, especially when rewards are immediate and emotionally charged (and this is consistently backed up in 2016, 2021, and 2024 as examples)

Moffitt’s (1993) landmark paper explains how adolescence-limited antisocial behavior is an “adaptive” reaction to the maturity gap - teens feel adult-like but lack adult privileges.

Teens with high sensation-seeking tendencies but strong parental monitoring showed fewer long-term behavioral problems (Mann et al., 2015).

The Life Span Wisdom Model

The Life Span Wisdom Model (Romer et al., 2017) reframes adolescent risk-taking as part of a developmental learning process. Here’s the core idea:

Adolescents aren’t just impulsive - they’re exploring.

They rely more on verbatim reasoning (literal, surface-level decisions based on facts and immediate rewards).

With age and experience, people develop gist-based reasoning - a more intuitive, big-picture understanding of risk that favors long-term outcomes and values.

Risky behaviors in adolescence provide experiences that help shape this “wisdom,” even though it sometimes leads to mistakes.

So, in this model, some risk-taking is functional, not just a flaw. It’s how teens gather data about consequences and build the abstract reasoning that adults rely on.

Key takeaways:

Adolescents take more calculated risks, not always because of poor control, but because they weigh risks differently.

Over time, life experience leads to “gist reasoning,” which helps people make faster, safer decisions without needing to crunch every detail.

Supporting teens means guiding their experiences - not eliminating risk entirely.

Long Story Short

Teens aren’t reckless because they’re broken, instead they’re taking developmentally appropriate risks. Most are trying to feel grown-up, fit in, or explore boundaries.

But when parents provide structure, empathy, and guided independence, teens learn to take smart risks—the kind that builds maturity rather than danger.

Not All Risk is Bad

Taking risks helps teens:

Explore independence

Build identity

Learn limits

Develop confidence and resilience

Quick Takeaways

Risk-taking is normal, not pathological - especially during adolescence.

Teens have overactive reward systems (the brain’s gas pedal) and still-developing self-control (the brain’s brake pedal).

Most risky behavior is temporary and peer-influenced, not predictive of future problems.

Parental monitoring, open communication, and scaffolding safe independence help buffer against dangerous risk.

When in doubt: connect, stay curious, and co-create boundaries.

Thank you for this. Essential for all parents and educators to understand this. I have worked in many school systems that try to eliminate all risk- which is understandable given the size of schools and need to maintain a stable organization. But an awareness of the developmental function of risk can still inform how educators interact with students on a daily basis.